Sep

2016

Are Some Bond Issues Equities Masquerading as Debt?

DIY Investor

1 September 2016

As part of its ongoing campaign to see investors better educated, RBE’s Mr Bond lifts the lid on some of the markets worst excesses.

The previous article, (‘Not all Bonds are Born Equal’ – DIY Investor 22nd July) mentioned the Prospectus Directive, the basic rule book governing the issuance of new securities to investors. Under the PD there are two types of bonds, Corporate Bonds and Asset Backed Securities (“ABS”).

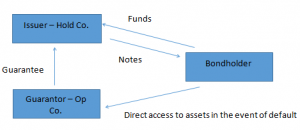

A Corporate Bond can be issued by any type of non-government entity. The issuer will be a PLC, or the overseas equivalent, and will have two years audited accounts. In some instance the issuer will be a new company, likely a hold co., in which case the two years accounts will be provided by an op co beneath it:

The key points here are:

- The accounts provide information that allows investors to judge the risks inherent in an issue, and provides the numerical raw material for the financial covenants.

- Should there be a default investors have access to the issuer assets, except those specifically excluded by pledges, e.g. bank guarantees, or mortgages.

Asset Backed Securities (“ABS”), are notes backed by financial assets. Typically these assets consist of receivables such as mortgages, credit card receivables, or auto loans. ABS differ from most other kinds of notes in that their creditworthiness derives from sources other than the paying ability of the originator of the underlying assets.

Financial institutions that originate loans—including banks, credit card providers, auto finance companies and consumer finance companies—turn their loans into marketable securities through a process known as securitisation.

Mr Bond warns, ‘Don’t take shareholder risks for bondholder rewards’.

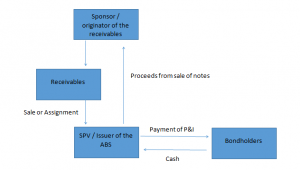

The loan originators are commonly referred to as the issuers of ABS, but in fact they are the sponsors, not the direct issuers, of these securities.

These financial institutions sell pools of loans to a special-purpose vehicle (SPV), whose sole function is to buy such assets in order to securitise them, the SPV is the actual issuer of the bonds.

The key points are:

- Bondholders have access only to the SPV’s assets, i.e. the securitised loans, referred to as collateral, which are the only assets of the issuer. You should expect credit enhancement by over-collateralisation

- Bondholders are wholly dependent on the cash-flows from the collateral to service coupons and the repayment of the loans underlying the collateral to repay principal.

As a simple summary, a corporate bond has two years accounts to support it, an ABS has hard assets, collateral, to provide the cash-flows to service coupons, the collateral is self-liquidating which provides the capital to redeem the bonds.

What we are seeing coming to market fits into neither category, many of these firms are start-ups with no financial history, often borrowing money to buy assets that ultimately collateralise the issue.

New firms with no operating companies to act as guarantor should not be issuing debt, if they need funds it should be shareholder equity. Equity investors, especially those looking at smaller businesses expect risk, in return they expect rewards; a suitable reward isn’t a 7% coupon it is the share price doubling or tripling. All that happens when these new businesses issue debt is all the risk is passed to the bondholder, if they succeed the owner of the business still holds 100% of the equity.

Mr Bond says ‘No coupon can compensate for the risk you are being asked to take’

Firms borrowing to acquire assets run the risk of either not being able to do so, or rushing and buying badly. If the issuer cannot acquire assets, after a year they will have had to pay one or two coupons, if the annual value of this is 7% then they will have diminished the bonds capital begging the question, “how do they return 100”?

Alternatively, rushing to acquire assets to service coupons can lead to mistakes meaning the assets may not be of the quality to properly collateralise the issue.

Another thing we are seeing is property linked bonds, often these bonds sit behind senior debt from banks; the bond is junior and is a cheap way for developers to avoid expensive mezzanine finance or having equity investors.

Not only are the bonds junior there may be times when the underlying property values are not sufficient to collateralise the bonds, especially if property prices slow down. Not only are bondholders left unsecured they are being short changed; mezzanine finance can easily cost 12%+, and equity investors often expect IRR’s of 20%+.

In addition, Mr Bond says, there are other warning signs to look for:

- The Listing Venue: exchanges such as the LSE will not allow issues such as this, especially in retail denominations, instead they gravitate to listings such as Cyprus and Gibraltar: Mr Bond says, ‘Leave these as places to go on holiday’.

- Fees: the prospectus should show fees, either broken down or as a total. Anything in excess of 5% is too much, issues over £30m should be even lower. Also check to see how the percentage is calculated, e.g. if it assumes an unfeasible size of issuance such as £50 or £100m.

Mr Bond says, ‘Fee levels such as this mean someone is being paid at bondholders’ expense. Good issues don’t need this level of fees’.

Not only aren’t all bonds born equal, many should not be issued as debt; Mr Bond warns, ‘Don’t take shareholder risks for bondholder rewards’.

One response to “Are Some Bond Issues Equities Masquerading as Debt?”

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

[…] ‘Are Some Bond Issues Equities Masquerading as Debt?’ – DIY Investor 1st September 2016 […]