May

2022

Classic Investment Mistakes and how to Avoid Them – Part 1

DIY Investor

20 May 2022

Excess Returns: A Comparative Study of the Methods of the World’s Greatest Investors

Frederik Vanhaverbeke

KBC Asset Management

“A country of security analysts would still overreact. In short, even the best-trained investors would make the same mistakes that investors have been making forever, and for the same immutable reason – that they cannot help it.”

Seth Klarman

“There is nothing new on Wall Street or in stock speculation. What has happened in the past will happen again and again and again. This is because human nature does not change, and it is human emotion that always gets in the way of human intelligence.”

Jesse Livermore

These quotations from Seth Klarman, one of today’s most respected hedge fund managers, and Jesse Livermore, a legendary momentum trader of the 20th century, leave nothing to the imagination.

Investors – whether private individuals or professionals – repeatedly make systematic mistakes on the stock market. And many of these mistakes are caused by unconscious psychological forces that impel investors to take irrational actions.

The relatively recent academic discipline of ‘behavioural finance’ focuses on analysing the many psychological forces or biases that lead to investment mistakes but decades ago, countless top investors had already discovered the destructive power of the human psyche, and learned how to deal with it.

In my book Excess Returns: A Comparative Study of the Methods of the World’s Greatest Investors, I explain how the world’s most

successful investors set about beating the stock market and how they try to avoid the errors that other investors make.

successful investors set about beating the stock market and how they try to avoid the errors that other investors make.

They emphasise that successful investors (i) proceed through a superior investment method, (ii) implement that investment method consistently and with great discipline, and (iii) know how to cope with all sorts of (unconscious) psychological forces that steer them repeatedly on to the wrong course.

In Part 1 we look in more detail at a number of classic mistakes along the investment chain.

Classic Mistakes Across the Investment Chain

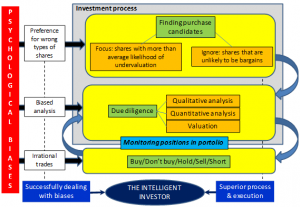

In figure 1, I illustrate the various steps in the investment chain, and the steps at which things can go wrong:

Step 1: Selecting shares for further analysis

Investors must use their time efficiently; it is impossible to analyze the many thousands of shares on the stock market so intelligent investors focus their efforts in the first place on analysing shares that have a greater chance of being undervalued than other stocks. Unfortunately, as illustrated in figure 1 there are a number of (psychological) forces that steer people to precisely the wrong shares. For instance, many people seem to find it logical to put their money in shares that figure prominently in the media, that do something spectacular, that come to the market for the first time or that are ‘hip’. Unfortunately, these sorts of shares are often expensive or over-hyped; top investors find the most interesting shares are actually those that people aren’t looking at, that aren’t popular or that people have an aversion to.

Figure 1: The challenge facing investors.

Step 2: Analysing the idea

Once a share has been selected for further examination, the serious investor has to find out whether it really is an interesting investment by looking at financial information in the annual reports, assessing the business’s competitive position, trying to form a view of the management and estimating the company’s intrinsic value.

However, here too, a number of psychological forces lurk which can jeopardise the value of an analysis – e.g.

• It is not unusual for an investor to form a certain (positive or negative) view even before the real analysis. You may, for example, have a positive bias towards a company whose name appeals to you or that sells the type of products you are fond of. Such preconceptions make it harder to make a neutral evaluation of the company if the investor then goes looking for evidence to confirm this view and to dismiss counter-arguments.

• Another typical example is that some people buy shares in the company they work for without hesitation as they consider themselves insiders who know a good deal more than the average person about what exactly is going on in the company. More often than not, that’s an illusion. Not doing your homework because you think you know a company inside out, whereas you don’t even know the most fundamental financial information on it (the position of most employees), can be a serious error.

Step 3: Buying and selling

In the last phase of the investment process, a decision has to be taken on whether or not to buy the share that you’ve analysed. Or you need to take regular decisions on whether to keep, sell or buy more of the shares already in your portfolio. This may seem easy but can be very difficult in practice because countless psychological forces often lead to irrational buy and sale transactions. For example, numerous investors refuse to buy stocks in a bear market, even if they’re quoted at prices that they could have only dreamed of in a previous bull market.

My book Excess Returns: A Comparative Study of the Methods of the World’s Greatest Investors goes into great depth into the above steps of the investment process. In so doing, I look at the way in which a wide selection of very successful investors operate and how their approach to the investment process sets them apart from less successful investors.

In Part 2 I look at a number of classic buy and sell mistakes

Commentary » Equities » Equities Commentary » Equities Latest » Financial Education » Take control of your finances commentary » Uncategorized

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.