Aug

2022

ETF closing down – what now?

DIY Investor

30 August 2022

Time and again, ETFs are merged or liquidated. What you need to know when your ETF is closing down or being merged – writes Jan Altmann

Occasionally an unprofitable ETF is closed by its provider or two similar ETFs may be merged.

The most important thing is that you don’t lose your money if an ETF is liquidated. It doesn’t wipe you out as if the share price plummeted to zero. Still, you need to know what happens when an ETF is closed or merged because it can cause a tax event and/or leave you out of the market for a short period.

When an ETF is closed you will receive the net asset value of your ETF shares as a cash sum (including distributions), if you don’t sell up before the final exchange trading date. In other words, you’ll get the market value of the underlying assets when the provider has them sold, minus items such as transaction costs.

In the case of a merger, you’ll automatically receive shares in the new ETF that are equivalent to the value of your shares in the old ETF (although the number of shares may vary).

Both scenarios count as a disposal for capital gains tax purposes and can, therefore, cause you to pay tax on the gain unless your ETF is safely sheltered in your ISA or SIPP, or the profit is covered by your capital gains tax allowance or can be offset using a loss.

European-wide fund legislation governs ETF closures and mergers, and the regulatory authority for your ETF’s domicile must approve the process.

It can take several working days for an ETF provider to work through the closure process and return your cash to your platform which then credits your account.

If the price of similar ETFs has risen in the meantime then you’ll get fewer shares for your money. This cost is rarely so dramatic that it’ll make much difference to your long term results but occasionally large market moves can happen in a couple of days – witness the price volatility of many ETFs during the coronavirus bear market and recovery.

For that reason, your ETF provider may encourage you to sell your holdings and reinvest your cash before your ETF’s final trading date.

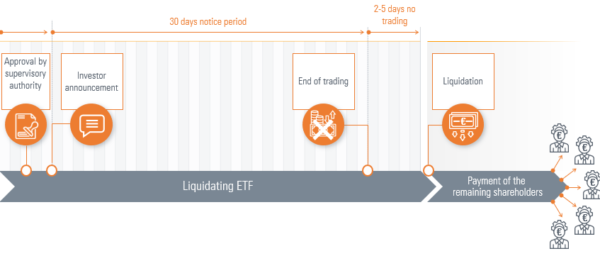

If an ETF is liquidated then you should be informed 30 days in advance of the planned closure.

Why ETFs close: lack of fund volume

If an ETF hasn’t scaled in terms of assets under management then it can be deemed unviable by its provider. That may happen if an ETF doesn’t prove popular enough to attract a critical mass of investors and so can’t achieve profitability (lack of fund volume).

ETF closure process

Why ETFs close: share classes

Sometimes it’s one or more of an ETF’s share classes that are terminated. ETF share classes are variants of the fund that may differ by fees, trading currency, stock exchange listing, or income distribution method. They’re like different avatars of the same fund.

When a share class is liquidated, the main ETF is not closed. The share class assets are instead moved to another share class of the same fund. This does not trigger a tax event because it doesn’t involve a legal change to the ownership structure. These transactions often occur at the end of an ETF’s financial year.

ETF mergers: the provider rationalises its product range

ETF industry competition and consolidation may cause one provider to buy or merge with another. iShares took the Credit Suisse ETF range off the Swiss bank’s hands several years ago and, more recently, Lyxor gobbled up the ComStage ETFs.

Often these acquisitions create a product range overlap that prompts the merger of similar ETFs.

Note: Lyxor has listed details of the ComStage ETF merger in the Notice to Shareholders section on its website

- Provider A buys provider B.

- Provider B’s FTSE 100 ETF merges with provider A’s FTSE 100 ETF.

- You own 100 shares in provider B’s merging ETF.

- Your ETF’s share price is £25 on the merger date. Your total holding is worth £2500.

- The share price of provider A’s receiving ETF is £50.

- The exchange ratio is 1:2 so you receive 0.5 shares in the receiving ETF for each share you had in the merging ETF.

- You receive 50 shares in the receiving ETF. 50 shares x £50 = £2500.

- Your total holding remains the same in value although the number of shares has changed.

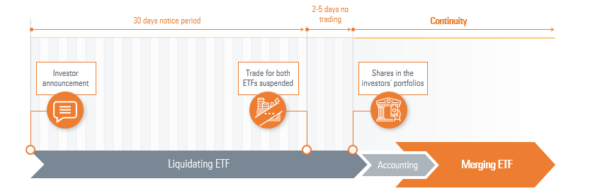

ETF merger process

Sources: justETF Research, UCITS Guidelines, KAGB, fund brochures

Investor notification is mandatory

You’ll receive an official notification from your provider via your platform when your ETF is being closed or merged. This notification features the key deadlines that affect you.

The notification will have been approved by the ETF’s regulator and will seem quite legalistic and technical.

Notifications will also be posted to the provider’s website and to news aggregators such as investegate.co.uk.

You should be sent the Receiving ETF’s Key Investor Information Document (KIID), too.

If you hold the Receiving ETF instead of the merging ETF then you’ll also be notified so you know when your ETF can’t be traded as the merger completes.

Merging ETFs: should I sell?

The merging ETF can be sold on the Exchange until a few days before the merger date. The closer the date gets, the more difficult it is for the market makers on the exchange to provide low bid-offer spreads due to the reduced availability of the ETF’s shares.

If you want to sell then try to do so at least one week before the merger date.

Otherwise, two other key variables may influence your decision:

1. ETF merges with a different fund domicile – tax disadvantage

If the two ETFs are domiciled in different countries then the tax authorities treat the merger as a sale and purchase of shares. This means that you’ll be liable for capital gains on the profits you’ve accrued up to that point on the merging ETF if it’s held in a taxable account.

Of course, you can defuse those capital gains by using your Annual Exempt Allowance or offsetting them with a taxable loss as usual.

An ETF’s domicile is revealed by the first two letters of its ISIN code. Here are some of the country codes you’re most likely to see:

- IE = Ireland

- GB = Great Britain

- LU = Luxembourg

- FR = France

- DE = Germany

- CH = Switzerland

- GG = Guernsey

- IM = Isle of Man

- JE = Jersey

- US = US

2. ETF merges with its non-identical twin

Always make sure that the Receiving ETF’s objectives and key features are suitable for you. Check the following:

- Index tracked: same country/regional coverage?

- Fees: does the receiving ETF have a higher OCF/TER or higher transaction costs?

- Number of holdings: Is the ETF as diversified as your old one?

- Distribution policy: Switch from distributing to accumulation/capitalising or vice versa?

- Replication: Change from physical to synthetic replication or vice versa?

- Sustainability: comparable sustainability criteria and rating?

- Securities lending: does the policy differ and are you comfortable with that?

- Tax status: Make sure your new ETF has UK Reporting Status.

- Factor strategy: the index’s factor strategy is close enough?

- Average duration (bonds): material change to your duration exposure?

- Average credit quality (bonds): do the holdings conceal lower-quality bonds?

- Average yield-to-maturity (bonds): are your expected returns similar?

ETF providers bear most of the costs

The good news is that the costs of ETF mergers are largely borne by the ETF providers. Only the transaction costs associated with liquidating an ETF are paid by investors to some extent. These expenses reduce the ETF’s NAV and you don’t pay anything directly. Typically the cost shaves a few tenths of a per cent from the NAV.

Commentary » Exchange traded products Commentary » Exchange traded products Latest » Latest » Mutual funds Commentary

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.